No. 44/45, Winter/Spring 2010

The Mennonite Brethren Church: How It All Began

When the Mennonite Brethren Church was born in 1860, few participants in that momentous event could have imagined that 150 years later, this renewal movement would claim membership in countries encompassing the entire globe. It is appropriate that we pause to reflect on God’s grace to our faith community in its earliest years.

Throughout its history the church has given birth to determined efforts to recall the church to its God-given mission. Change has sometimes been inspired by strong personalities; at other times, entire groups have emerged to call believers back to a life of active faith and commitment to Christ.

Delegates at the Conference of Mennonite Brethren Churches in May 1910. Russian government observer in front row.

The Mennonite community has been no exception to such renewals. In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, significant numbers of Mennonites found a home in South Russia. Here they lived in their compact communities, the Khortitsa and Molochna colonies, with a large measure of self-government and growing prosperity. They were granted broad privileges to accommodate their faith. These included exemption from military service, the right to have their own churches and schools, retain their language, and have temporary exemption from taxation. The resulting interwoven social, administrative and church structures created somewhat closed communities that differed from the traditional Anabaptist–Mennonite emphasis on separation of church and state.

Other similar settlements soon followed, both in European and Asiatic Russia. It was in this context that a number of spiritually-concerned persons began to lament that religious observance too often had become ritualized and pro forma, lacking the earlier vitality that had characterized the 16th century Anabaptist–Mennonite movement. At the same time, ministers such as David Epp in Chortitsa and August Lenzmann in Molochna, called for a more vibrant faith and engagement with the larger Christian community. At the same time, they hoped for reform from within.

Voices of renewal echoed throughout many of the villages. Encouragement came from Lutheran pietists who lived in Neu-Hoffnung, a village just south of Molochna. Their minister, Eduard Wüst, had a powerful impact on the Mennonite community. Wüst called for repentance, conversion, and a life of discipleship. His message was echoed by concerned persons in a number of Mennonite villages who now led a move to revitalize the churches. In response to such sentiments, a group of determined champions of renewal arose, and in discussions with church leaders, asked for more frequent observance of the Lord’s Supper, also in private homes, and for more emphasis on a God-honoring lifestyle. They felt that too often mere church membership was viewed as sufficient.

The renewal movement gained some influential supporters. In late November 1859, some met in the home of one of the members and celebrated the Lord’s Supper. This event caused strong displeasure and opposition by a number of church leaders, who felt that such a step was inappropriate and divisive. The participants, however, contended that efforts to restore spiritual vitality were absolutely essential.

Johann Claassen, who negotiated the recognition of the new movement.

As further expression of that determination, on 6 January 1860, eighteen persons met in the home of Isaak Koop in the village Elizabethtal and issued a call for a return to the practices of “our dear Menno.” They drew up and signed a document that called for a church of committed believers, baptized upon profession of faith and determined to be disciples of Christ. In the heat of the moment, some harsh denunciations of the “decadent church” from which they were withdrawing created serious tensions with the larger Mennonite community. Some of the charges brought against the mother church were, as historian John A. Toews has commented, “far too sweeping and too severe in character.” A number of leaders in the parent church admitted that a deeper spirituality was badly needed, but they regretted that a new movement had been formed. From their perspective, renewal could best be fostered from within a movement. But the champions of a new approach felt called and were deeply committed to lead the way to a deeper life of faith. Three of the signers, Abraham Cornelsen, Johann Claassen and Isaak Koop were appointed as official representatives of the new movement.

Many leaders of the larger Mennonite community condemned the group as being self-righteous and divisive; others, however, even though they did not join the dissidents, lamented that charges of a lack of spiritual vitality and health were often only too true. Such leaders agreed that change was badly needed, but they questioned the wisdom of creating a division and thus polarizing the community.

Determined opposition by some leaders of the traditional position led to efforts to declare the new movement an illegal departure from approved policies. As a result, Claassen made several trips to St. Petersburg, the Russian capital, to gain government approval, and also to secure official recognition as a body that remained part of the Mennonite community. It should be noted that some prominent traditional leaders, such as the evangelist Bernhard Harder as well as the elder Bernhard Fast warmly welcomed the new movement as a demonstration of divine grace, and defended its adherents, even though they themselves declined to join the dissenters.

While this renewal was growing within the Molochna colony, a similar development occurred in the sister colony in Khortitsa. There systematic Bible study, as well as visits by the Baptist minister J. G. Oncken from Hamburg, encouraged the reform, and in 1862 advocates of renewal formed a new congregation in the village Einlage. Abraham Unger, a resident of the village, emerged as leader and elder, and authored a confession of faith for the new movement. This statement evidenced the significant influence of Baptist beliefs. Strong cooperative ties developed between the new groups so that for a time leaders considered forming a united Mennonite–Baptist group, but this suggestion was soon dropped. Another visiting Baptist minister, August Liebig, spent some time in Khortitsa and helped to form harmonious relations between the two groups as they agreed to retain their separate identities. Liebig also introduced Sunday schools into the new movement.

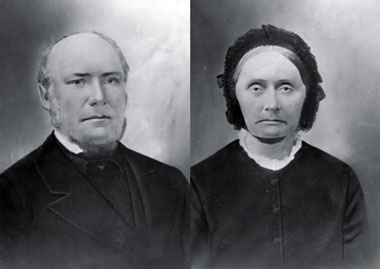

Abraham Unger, Elder of the Einlage (Chortitza) MB Church and Katharina (Martens) Unger.

Meanwhile, the new groups determined to establish their own identity. Representatives traveled to St. Petersburg to gain official recognition. Here the authorities asked for a confession of faith, in Russian and German, and a full explanation of Mennonite distinctives. These were provided and in 1880 authorities issued a statement confirming the new movement as part of the Mennonite faith community. Soon thereafter, two educators in the Molochna colony, Johann Wieler and Peter M. Friesen, were commissioned to prepare a more comprehensive statement of belief and practices; the result was the “Mennonite Brethren Confession” of 1902. This document was signed by ministers of various congregations, now spread far beyond the borders of the original two “mother colonies.” It echoed traditional Anabaptist–Mennonite doctrines and, unlike earlier Mennonite confessions, called for baptism by immersion, a practice begun in 1860 when Jacob Becker, an early adherent of the new movement, baptized Heinrich Bartel.

The Mennonite Brethren church soon gained members in various parts of the Russian empire. The first Mennonite Brethren General Conference was held in 1872 and on this occasion, five itinerant ministers were appointed to nurture members in scattered groups of believers. In many instances, these consisted of house churches found in widespread Mennonite villages. Very soon, however, Mennonite Brethren began building churches. One of these, a large, impressive structure in the village of Rückenau, soon emerged as the center of Mennonite Brethren church life in Russia.

Another Mennonite renewal movement arose, this time in the Crimea in 1869. Led by Elder Jacob A. Wiebe, it took the name “Krimmer (Crimean) Mennonite Brethren Church” and in 1874 the members immigrated to Kansas, where they established the Gnadenau church. Soon members spread to other states as well, and founded a number of sister congregations, usually known as the “KMB Church.” In 1960 it joined the Mennonite Brethren Church of North America.

Now, 150 years after its beginnings, the Mennonite Brethren Church has expanded far beyond its early ethnic boundaries and become a global faith community. Mennonite Brethren will celebrate this occasion in many countries during 2010, seeking to renew their commitment to faithful discipleship.

Further reading

-

Abe Dueck, Moving Beyond Secession: Defining Russian Mennonite Brethren Mission and Identity

-

Abraham Friesen, In Defense of Privilege

-

Peter M. Friesen, The Mennonite Brotherhood in Russia, 1789–1910

-

John A. Toews, A History of the Mennonite Brethren Church

-

Paul Toews and Kevin Enns-Rempel, For Everything a Season

-

Paul Toews, ed., Mennonites and Baptists